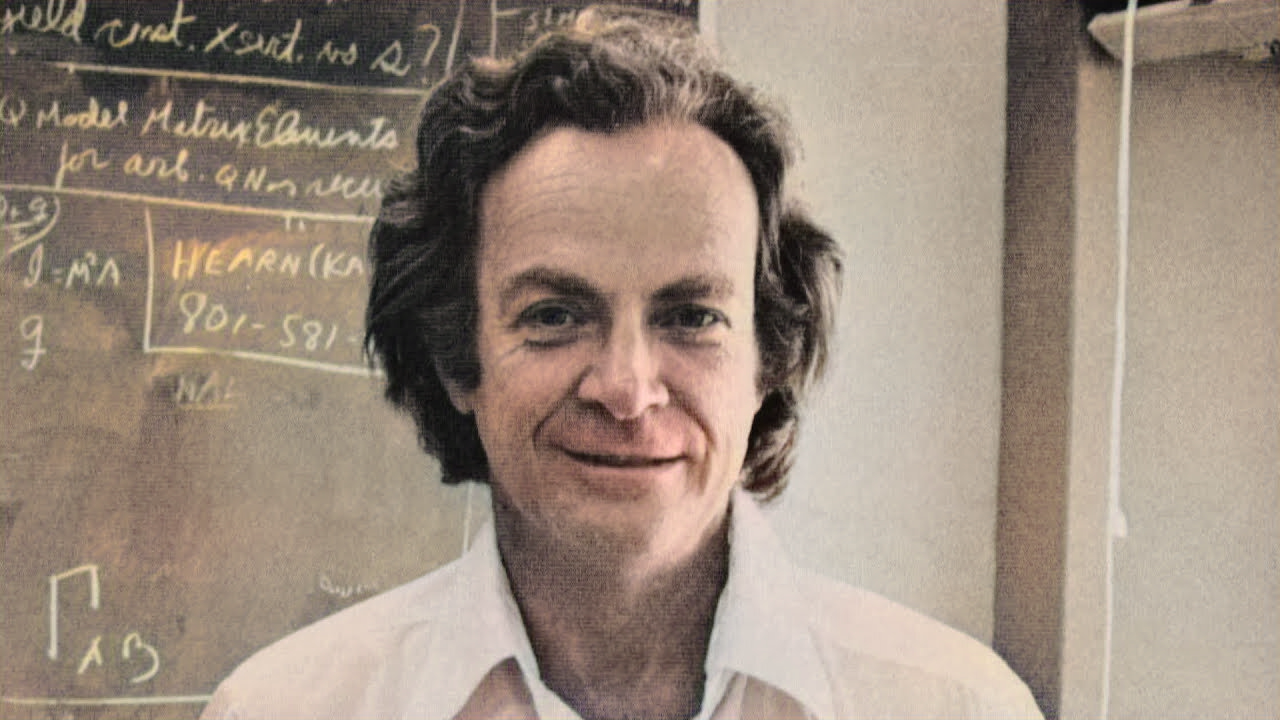

We all know Richard Feynman as a Nobel Prize winner and a beloved teacher whose lectures on physics are enjoyed by millions of people. It would be interesting to know how Feynman became so imaginative and curious about the world. How did Feynman learn physics and mathematics? Let's find out in this post.

When asked in an interview, if anybody could become a physicist like him, Feynman candidly replied: "Of course. I was an ordinary person who studied hard. There are no miracle people. It just happens. They got interested in this thing and they learned all this stuff."

The young Richard Feynman was largely influenced by his father, Melville Feynman, who encouraged his son to ask questions and challenge orthodox thinking. Melville was a sales manager but he always wanted to become a scientist himself.

Feynman recalled: "The most important thing I found out from my father is that if you asked any question and pursued it deeply enough, then at the end there was a glorious discovery of a general and beautiful kind."

Feynman also learned from his father the difference between knowing and understanding. For instance, you can know the name of a bird in all the languages of the world, but when you're finished, you'll know absolutely nothing whatever about the bird.

Feynman goes on to comment: "I don't know what is the matter with people: they don't learn by understanding; they learn by some other way – by rote or something. Their knowledge is so fragile."

When Feynman found a subject which interested him, he was not the kind to wait for the right teacher to come along; Feynman was determined to master the topic by himself. This is how he practiced early on the art of teaching.

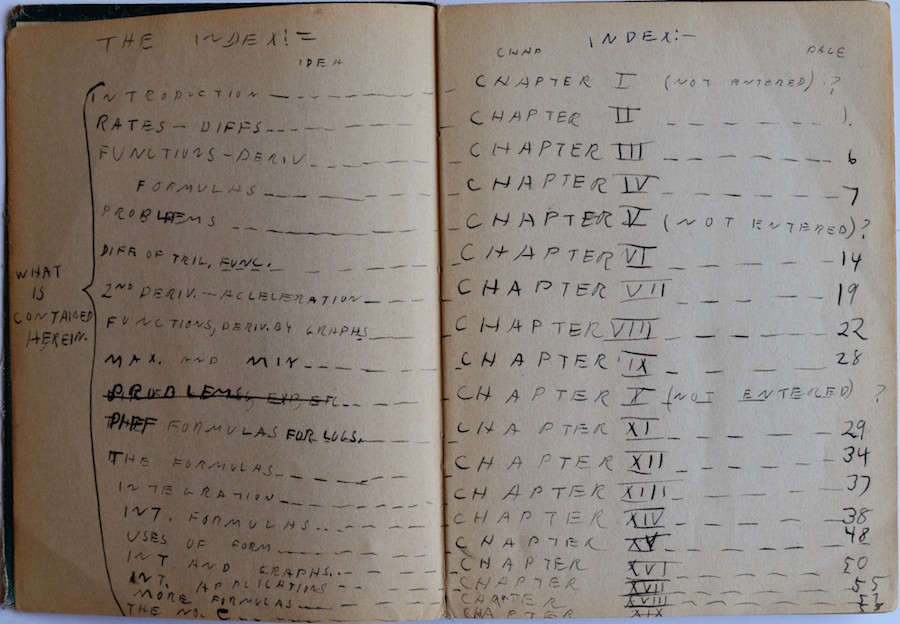

For example, Feynman self-studied calculus at the age of 14 by reading Calculus for the practical man. This and other books written by James Edgar Thompson, such as Algebra for the practical man intrigued him.

|

| Table of contents. Picture credit: Melinda Baldwin |

Physics, astronomy and science history blog for students

Physics, astronomy and science history blog for students